Hi! This is a story about Trade. We're building a commodity exchange in Ghana, and we've started with trading maize. In our first ten months of operation, we've traded over $1.2M worth of goods. This is what our team looks like today.

We wrote this story in an attempt to inspire people to join our team. Feel free to skip to the job listings at the bottom :)

The original goal of Trade was to build an SMS-based commodity and transport exchange. A 2012 study showed that in Ghana, 40 - 70% of the final price of agricultural goods was going to middlemen. We wanted to create a platform, accessible to all types of phones, that would allow buyers, sellers, and transporters to contract and exchange payment for goods and services.

This is how we thought it would work. (I’m going to call this v1 from now on.) Farmers would text in offers and buyers would text in bids. If there was a feasible match, we would contact transporters to get their price. If the price including transport was feasible, we would contact the buyer and seller to confirm. If they confirmed, the buyer would transfer the money for the trade to us. On pickup, the seller and transporter would text in to verify that the transaction was taking place, and the seller would be paid via mobile money. On delivery, the transporter would be paid via mobile money.

We won a grant from the Gates Foundation to work on this.

We began in Tamale, Ghana.

And to begin, we focused on sellers. Supply is disparate in Ghana, spread amongst a lot of small producers. So we decided to run transport ourselves and manually sell to whatever buyers we could and focus on developing the platform for sellers.

This is a photo from our very first trip to a village, in September 2016. We wanted to take photos of farmers so transporters could verify their identity on pickup.

Dauda and Mohammed are holding the background and Hannah is taking photos.

The first problem with v1 was that a lot of farmers are illiterate and so couldn’t use SMS. To accommodate, we built an automated-voice platform that allowed them to place orders, e.g. “press 1 for maize,” “say your price.”

Shafiq making the Dagbani voice recordings for the phone line.

We launched this platform October 1st of last year. Here is a photo of a big presentation we did explaining it.

Excitement was high. People were enthusiastic about the platform and about 40 people called in that night to test placing an order. Some people called it for fun, because they had never heard an automated line in Dagbani before.

The problem, though, was that farmers were just beginning to harvest, and so it was too early to buy large quantities. That first week, we traded 2 bags of maize.

Photo from our first day of trading.

We sold these bags in the Tamale market, and showed the voice line to the buyers when we did.

“Don’t tell anyone else about this,” they instructed us.

Over the next weeks, we received more calls (89 in the first two weeks) and traded more bags. Supply was still low pending harvest, but we were able to grow our bags traded each week.

Photo from our second week trading.

Happy buyers

A chicken farmer.

A food processor.

As we traded and tried to grow faster, we started to find other issues with v1. The biggest issue was that farmers waited to sell their goods until they needed money, which meant whenever they wanted to sell, they wanted to sell very quickly. They did not have time to place an order and wait for us to find a buyer.

Around that same time, we traveled to Kumasi, six hours south of Tamale, where there are a lot of larger buyers.

Meeting with the poultry farmers association in Kumasi.

The volumes that the buyers in Kumasi were buying dwarfed what our sellers were selling. Some of these buyers were buying 1,000 bags a week. Many of our sellers would sell 80 bags in a year.

It became clear to us that in order to satisfy the seller’s want to be paid immediately and also to aggregate enough supply to satisfy bigger buyers, we needed to find a way to buy everything all of the time. This meant two things: 1. Deciding a trading price that we would buy at and take price risk until we found a buyer. 2. Storing bags.

We started storing bags on the front porch of our office, which was also where part of the team lived.

This photo is from a few months later, but you get the idea of what this looked like.

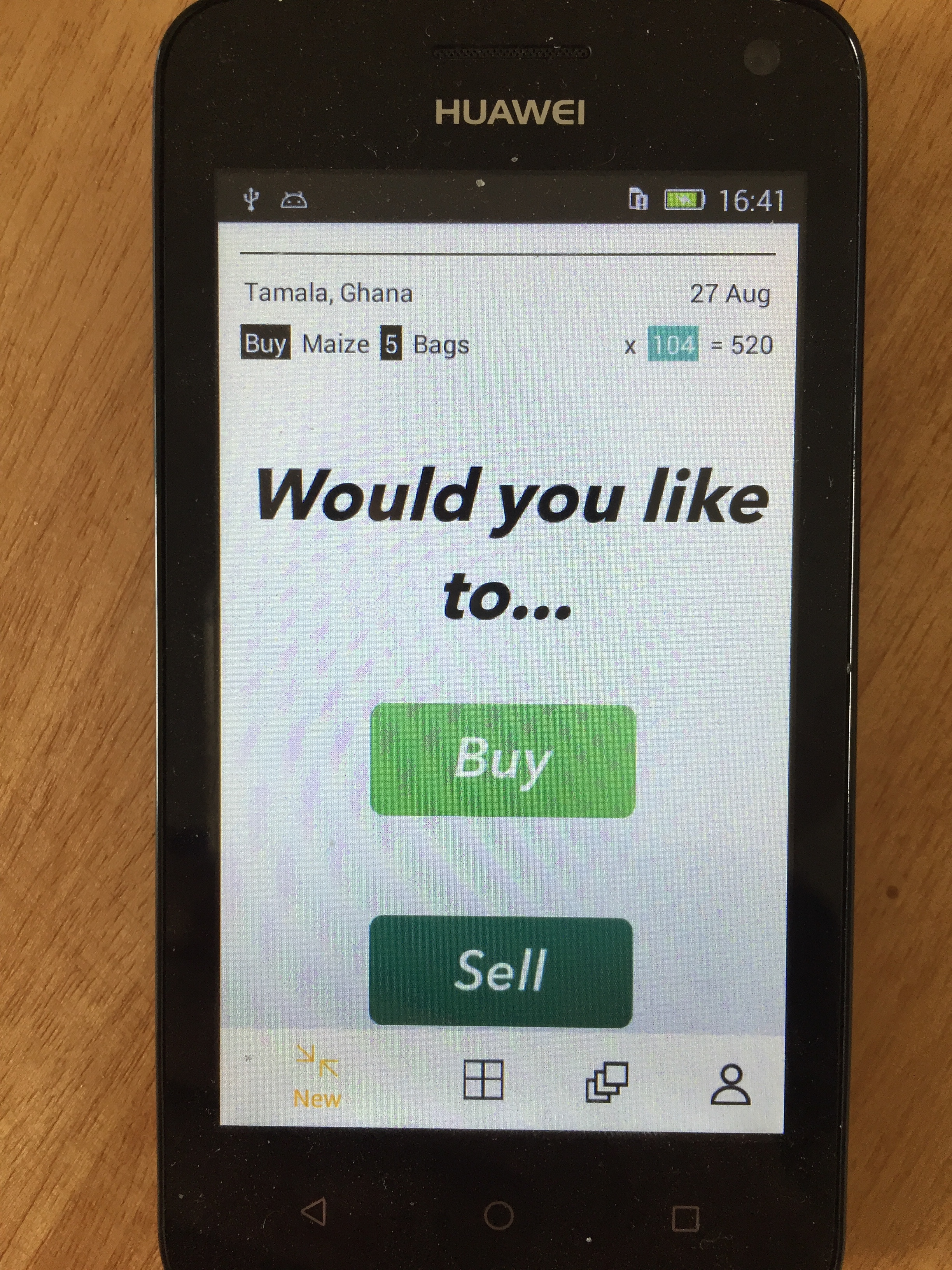

Around this time we also launched an app for our buyers who had smart phones. This was an early version.

However, we soon realized we didn’t really understand our buyer’s needs or our product well enough yet, and we shelved the buyer app and continued focusing on the supply side.

So we no longer waited to find a buyer before buying bags. As soon as a farmer placed an order, we would call them back and tell them that we would buy it. But still, sometimes we were not fast enough. A farmer would call us at 3PM, and maybe we would be out. We would call them back the next morning to say we were going to come and get the bags, and they would say they already sold it.

We wanted to find the extreme: what is the closest we could possibly be to the farmers? In a few villages, we decided to give cash to a trusted person and just let them buy any bags. Then, once a week we would come and collect the bags. It worked really well. We got a lot of bags from a lot of sellers really quickly.

So we knew the extreme, and that farmers (obviously, in hindsight) really valued convenience and quick payment. But we were not sure that this was the best way to grow. We started thinking about ways we could provide farmers a more convenient and reliable experience without just putting cash in the village.

The changes we made spanned into January, and around that time several new key people joined the team.

Anson and Edna

and Dave

Trade had also been accepted into Y Combinator’s Winter 2017 batch, and so part of the team would be back and forth between San Francisco and Ghana January through March.

In January, we changed a lot of things.

First, to try and provide a more convenient experience to farmers, we decided to start working more directly with transporters who lived in the villages we worked in. When we presented in a village, the farmers would pick a transporter that they trusted enough to carry cash back to them. Once chosen, we would have this transporter go through a training with us, where we would teach them how to inspect the quality and weight of the goods. After the transporters were taught how to check weight and quality, we would put them on a schedule, coming two days a week from their village. We would pay them a fixed rate, whether they had 1 bag or 20, and they would take cash back to farmers. We hoped the consistency and convenience of this would attract more sellers.

A transporter training day.

Finding a way for them to check the weight was particularly tricky. We thought creating and enforcing agreed upon standards, in doing so creating a common vocabulary for trade, was important and that meant weighing was very important. For a while, we had tried giving simple mail-room type scales to someone in a villages or carrying them with us when we went to pickup bags. However, these scales broke and, even when working, were a bottleneck.

We had a breakthrough when we realized that we could draw a fill line on the bags at the point where the average 50kg bag was filled. Surprisingly, this was a very good proxy for weighing and there was little variance between bags.

In the next months, we spent A LOT of time drawing lines on bags.

Cardboard “rigs” for drawing lines on bags.

Around this same time we finally had to acknowledge that the voice platform wasn’t working. Farmers would call it once, and then we would return their call from our personal line. From then on, they would always call our personal line. Again, obvious in hindsight, people want to talk to people, not a recording.

And the transporter schedule did not help. We thought farmers would be calling our platform and we would relay the information to the transporters. But the farmers and transporters already knew each other, why would they waste money and time calling us? They would just talk to the transporter directly.

The failure of the voice app meant a lot of lost data. Since people were supposed to place their orders through the platform, we delayed too long in developing a way to track orders that were placed to our personal lines, as almost all orders were, even in October.

Simultaneous to recognizing this failure, the partners at Y Combinator pushed us to realize that we were doing a lot of future solving: thinking about how the platform would or should work with thousands of people using it, and not focusing on the problems we had today. They pushed us to grow a lot faster, trade 1000 bags in January, and let growing reveal the actual problems.

So we ripped out basically all that we had built and started from scratch. The voice line would now just give a price quote for our current price at our Tamale warehouse. And all orders and users would be tracked through Google Sheets.

Trading a 1000 bags in January was out of reach, but we traded 253 bags, up 257% from the month before.

Here’s a photo of the first “big shipment” we ever made, on January 18. Most of the bags were loaded by our team, starting at 12AM.

We started to grow really quickly. In part because of the time of year: a lot of farmers were now ready to sell. But also because we had built some structure to enable it. Drawing lines on bags and using transporters on a schedule allowed us to just focus on intake rather than needing to be in the villages. We had sort of figured out the simplest version of our value add: provide clear and transparent quality, weight, and price standards and pay immediately.

Our porch started to get really full.

So full that we got a warehouse

But by the end of February, our new warehouses was also overflowing

Photo of a shipment in February

You might be wondering how we were buying all of these bags with no confirmed buyers, and so no money to buy them. We had money from the Gates Foundation and Y Combinator, but at this point we had no bank account in Ghana to transfer it to, so we were trade financing by maxing our debit and credit cards, on a weekly basis.

In February, we started having problems with the transporter schedules we setup. Since we paid the transporters no matter how full their truck was, some started coming on their assigned day with one bag, and then they’d come the next day with a full truck, the farmers paying for transport.

We also realized, though, that now that we had started advertising our “door price”––the price we pay at our warehouse––we empowered people to find their own transport and sort the pay out amongst themselves. Some people had already started doing this, working outside of our assigned transporters in the village. We decided to end the schedule, and let farmers arrange transport for themselves, as they were better at it than we were.

We continued to grow really quickly through March. We opened more warehouses, but at one point everything was full and we had to go back to storing bags at the office.

Photo of a shipment in March.

Y Combinator officially ended in March, and we raised $750,000. Mostly from Sam Altman.

Many more amazing people joined during these months.

Growth was flat in April, largely due to some payment issues we started experiencing with buyers. We continued to try to get closer to the sellers and provide a more convenient experience, and so at the end of April and beginning of May we opened up two village warehouses, shown with the green circles in the image below. (The blue circle is Tamale, and the red markers are some of the villages that trade with us).

And we’ve moved to an even bigger warehouse in Tamale

In May growth picked back up. We traded 9842 bags, which means shipping the truck below about 25 times in a month.

In June we finally moved our office out of our living room.

And we started offering deferred payment contracts to farmers. Since our buyers want to pay over four or five weeks, rather than taking a loan from a bank (at 32% interest in Ghana) to finance the trade, we decided to offer our sellers interest for waiting to take payment for bags they sold to us. It’s been really popular so far, and we’re really excited about the structure’s potential for becoming a payment platform.

In July, we started operating in our second “supply hub,” Ejura.

The Ejura hub has grown really quickly. We traded over 3000 bags from there in the first month of operation, and we’ve really only been constrained by how fast we can take the maize in. It’s been exciting to see farmers in an entirely different part of the country equally enthusiastic about our product.

Dauda pitching farmers in Ejura

The main cause of the flat growth over the last few months, as far as we can understand, is that we’ve reached the end of the selling season in the north. Farmer's harvest in October and the final selling push is in June, when farmers sell to buy fertilizer. The first weeks of June were our largest ever, taking in over 1,000 bags in a day, but supply in the north has dropped since then.

That’s not to say that we haven’t been busy, though, handling 10,000 bags (1,000 tonnes, ~$260k value) of maize a month while opening an office in a new part of the country is operationally intensive. Our whole team is now about 30 people. A recent, partial team photo below.

Since we ripped all of our technology out and went to using Sheets in January, we’ve built a lot. We have three core categories of software/technical work: internal app, buyer facing app, and high level operations tooling.

Our internal app is our most mature product. Everything we do, from logging village locations to recording shipments, is either done through or recorded in the app. Data collected through the app gives us realtime metrics on warehouse operating capacity, seller and village retention, and much more. It is maybe the biggest reason we’ve been able to grow so quickly without folding.

We now have a much better sense of what our buyers want and what we can offer them. In July we launched a beta version of a new buyer app, and we are excited to fully launch it. It allows buyer to see our current inventory availability and delivery price to various locations, place orders, and track shipment and payment progress.

High level operations tooling is a bad name for an increasingly interesting and broad space of technical work related to statistics, operations research, actuarial science, and other fields. Our warehouses, transport, payment, and inventory models all border into broader fields that we can learn a lot from. We have started to do some work here––statistical quality control, payment prediction––and we are excited to do more.

We are confident dramatic growth will pickup again as soon as harvest comes, and the whole point of writing this was to inspire others to join us.

We’ve been able to grow so fast and connect so many people because we’ve become a trusted intermediary. People no longer know or care who they are trading with, they just trust Trade. Farmer’s trust that our standards and clear and fair and that our payment terms are reliable. Buyer’s trust that our weight and quality are consistent and that our delivery is reliable.

We think these underlying services, the engine of what we’re building, are really important and in no way limited to maize. If we say something is going to be “A,” it will be. If we say it will go from “B” to “C” at “X” time, it will. If we say we’ll pay on “Z” amount on “Y” day, we will. We think these are the essential services of a commerce platform that is going to allow anyone, anywhere to trade anything with anyone, anywhere.

We’ll start with trading food commodities and then move to other commodity-like goods: this season we’re going to allow farmers to sell us maize and keep their money with us for easy purchase of other goods, like fertilizer that will be delivered to them for free. Eventually we’ll allow anything to be bought and sold. And even if you don’t need us to find a buyer or a seller, you can use us to transport. Want to send a gift to your grandma in the village? We can do that. Want to get your product into every village in Ghana? We can do that.

In the coming weeks, we’re going to begin selling different grades of maize, something that, to our knowledge, no one has officially done in Ghana before. We think it will do a lot to help mature the market. We’re also going to build our own custom warehouse in villages. It will make us a more convenient selling option and is an important step to being able to make last-mile pickup and delivery guarantees. We’ll also begin providing very cheap storage for all types of commodities, which will give us a better idea of what commodities we should trade next and will also help us to coach farmers to placing market orders. You might be more willing to pick a price and wait for a buyer if at the moment you’re just concerned about storing your goods, not urgently getting money.